The Fight Against Hate Speech: Freedom of Expression vs. The Protection of Minorities

BY REBECCA TANG

Article 20 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) declares that "any advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence shall be prohibited by law.”[1] New Zealand has ratified the ICCPR however, as Minister of Justice Andrew Little claims, the current law targeting hate speech offences is “very narrow”.[2] Amidst the backlash of the Christchurch mosque terror attacks along with the general rise of white supremacy and alt-right extremism around the world, these dangerous shifts in society have highlighted the need for a review of New Zealand’s standing on hate speech laws.

This article will examine existing hate speech laws in New Zealand and discuss the implications of the recently proposed changes.

Background of New Zealand’s hate speech laws

“Hate speech” is not codified as an individual offence in New Zealand and is only an aggravating factor in sentencing.[3] It is not recognised as a legal term but is incorporated into racial discrimination legislation.

Under sections 61 and 131 of the Human Rights Act 1993, it is illegal to incite “racial disharmony” through “matter or words likely to excite hostility against or bring into contempt any group of persons…on the ground of the colour, race, or ethnic or national origins.”[4]

The Harmful Digital Communications Act 2015 may also be law relevant to hate speech as it aims to prevent harm caused to individuals through digital communications.[5] It is important to monitor the circulation of content that encourage prejudice or abuse against particular people in society, especially in the age of social media where information can spread rapidly.[6]

Following the events of terror in Christchurch, Andrew Little announced he would be fast-tracking a review that could widen the scope of what constitutes as hate speech and increase the severity of sanctions that could be imposed.[7] The primary concern with the current laws is how they only recognise hate speech when it is directed at race. Therefore, the current law does not protect other social groups, such as religion, gender or sexual orientation. The Harmful Digital Communications Act only protects the individual from harmful digital posts, and there is no mention of whether collective groups can be classified as the victim.[8]

Possible dangers of criminalising hate speech

Limiting freedom of expression

A major contention around hate speech laws lies in the boundaries of what should constitute as hate speech, balanced with freedom of expression. Law lecturer Dr Eddie Clark argues that it is difficult to determine the threshold of what equates to hate speech in a society where people have differing views and opinions. Restricting what can be said about different groups can close down debates on issues that should be open to discussion and as a result, undermine the democratic system, where contrasting views matter.[9]

For example, in a 2018 British case, a billboard displaying the definition of woman as “adult human female”, was taken down after Dr Adrian Harrop, an LGBT activist, claimed that it contributed to a hate campaign.[10] Yet, the creator of the poster, Ms Keen-Minshull, claimed that the poster was for starting a conversation about women’s rights and voicing her concern of how the term “woman” was “being appropriated to mean anything.”[11] Setting the implications of Ms Keen-Minshull’s views aside, it may be wrong to incriminate her opinion. In a democracy where there is value in people having differing opinions, the fear and uncertainty concerned with would be a criminal offence could silence the view of different sides in social discussions. Thus, we would be deprived of a comprehensive representation of what people believe in.

Preventing respect for the law

Given that freedom of expression is highly prioritised, an overreach of limiting freedom of expression may lead people to lose respect for the law. For example, if the state punishes someone on the ground of hate speech, but the people do not equate that person’s words to hate speech, the state would lose their status as an impartial, representative entity.

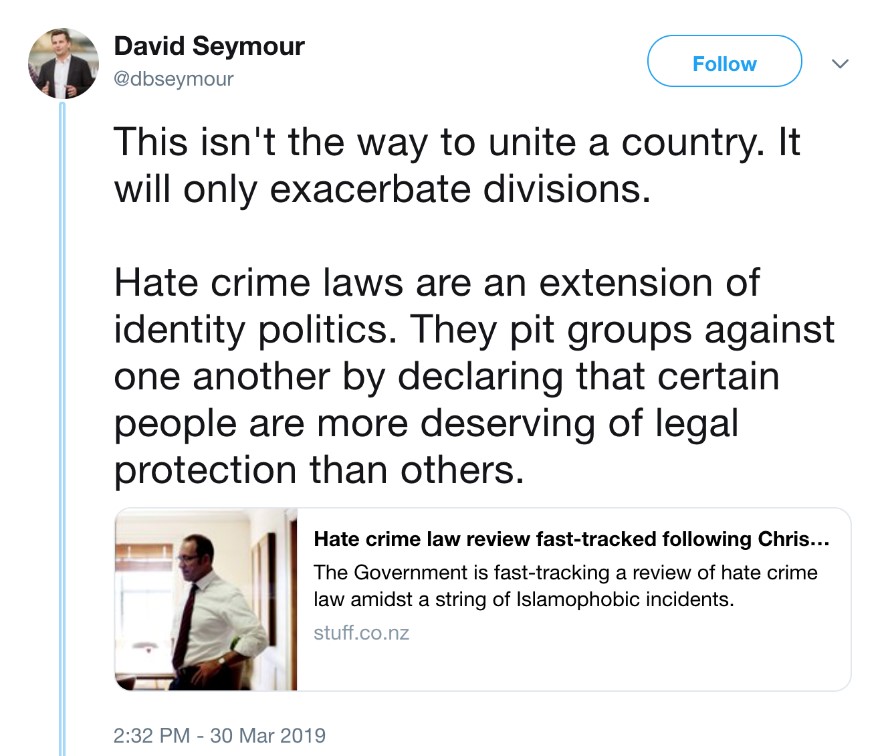

Furthermore, as ACT Party leader David Seymour contends, stricter hate speech laws are an extension of identity politics and could be more divisive and spark more hostile relations between people. The laws may imply that certain people are more deserving of legal protection and may backfire as they would put groups in opposition of each other.[12]

Image source: David Breen Seymour (@dbseymour)

Therefore, it is important to carefully consider the scope in which “hate speech” is defined, should Parliament aim to establish an individual offence promptly.

Can the right to freedom of expression be reconciled with hate speech laws?

As recognised in international human rights law, few rights are absolute and most are subject to reasonable limitations.[13] Freedom of expression, despite being strongly defended, certainly has its constraints. As Little asserts, it is important to remember that “freedom of speech and the protection of freedom of speech was always conceived of as a protection of the powerless against the powerful.”[14] One aspect in the law where freedom of expression can be overridden is in instances of defamation to protect individuals from the consequences of false information published about them.

Given that the individual is protected by the law from the implications resulting from the spread of false information, the same could apply to minority groups when information, that may lower their status in the eyes of society, is publicised. For example, if someone falsely states that person A has violent tendencies, person A would suffer stigma and condemnation from the public. Likewise, if someone makes the assumption and circulates that a particular group of people have violent tendencies, those who belong to that group would suffer similarly to the individual. The consequences of these types of assumptions could lead to loss of opportunities and in the extreme, hostilities directed at them.

Furthermore, the concern over defining hate speech and the possibility that hate speech laws can silence people and prevent them from expressing their own opinions could indicate the widespread ignorance towards the threat of claims that publicly place specific groups in a negative light. As McCauley and Moskalenko of the University of Pennsylvania recognise, political radicalisation is the escalating commitment to intergroup conflict. It occurs first, through the construction of an identity and then the build-up of beliefs that manifest in a perceived threat of another to that identity group.[15] Diego Muro, a lecturer of International Relations, identifies that the process of radicalisation can begin with simple exposure to ideas that may spark discontent towards a particular group of people.[16] Therefore, a supposedly innocent remark may contribute to a wider, more dangerous discourse.

Conclusion

The issue of hate speech is not a problem that can solely be solved from the top through legislation but a problem that must also be addressed from below. To prevent another incident like Christchurch, widening the scope of hate speech may be useful to publicly stigmatise the inducement of hostilities towards social groups. In turn, this would protect minorities and enable them to have a more equal standing in society. However, when people are accustomed to privilege, equality can feel like oppression. To address the what society would consider a reasonable limitation to freedom of expression, people must continuously learn about how expressions targeting social groups can be harmful. Parliament may not be able to make hate speech a single standing offence now, but society can indeed progress in that direction.

The views expressed in the posts and comments of this blog do not necessarily reflect those of the Equal Justice Project. They should be understood as the personal opinions of the author. No information on this blog will be understood as official. The Equal Justice Project makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this site or found by following any link on this site. The Equal Justice Project will not be liable for any errors or omissions in this information nor for the availability of this information.

Featured image source: pixabay.com

[1] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 999 UNTS 171 (signed 19 December 1966, entered into force 23 March 1976), art 20.

[2] Radio New Zealand “Current hate speech law 'very narrow' - Justice Minister Andrew Little” (3 April 2019) <www.rnz.co.nz>.

[3] Sentencing Act 2002, s 9.

[4] Human Rights Act 1993.

[5] Harmful Digital Communications Act 2015.

[6] Jacinda Ardern “Jacinda Ardern: How to Stop the Next Christchurch Massacre” (11 May 2019) New York Times <www.nytimes.com>.

[7] Above n 2.

[8] Section 22.

[9] Thomas Coughlan “What will happen to our hate speech laws?” (8 April 2019) Newsroom <www.newsroom.co.nz>.

[10] BBC News “Woman billboard removed after transphobia row” (26 September 2018) <www.bbc.com>.

[11] Above n 9.

[12] David Breen Seymour (@dbseymour) “This isn’t the way to unite a country” <https://twitter.com/dbseymour/status/1112105392664768512>.

[13] Australian Government Attorney-General Department “Absolute rights” <www.ag.gov.au>.

[14] Above n 8.

[15] Clark McCauley and Sophia Moskalenko “Mechanisms of Political Radicalization: Pathways Toward Terrorism” (3 July 2008) Taylor&Francis Online <www.tandfonline.com>.

[16] Diego Muro “What does Radicalisation Look Like? Four Visualisations of Socialisation into Violent Extremism” (December 2016) Barcelona Centre For International Affairs <www.cidob.org>.